Immediate not hot late trans take

Gender affirming surgery vs breast reduction mania in the New York Times

I cannot express, as a trans person, how deeply sad and righteously angry the New York Times article “The Power of the Smaller Breast” made me (guest link, should be ungated). I want to be transparent about my grief and anger, really SHOUT IT, to the point that this essay will be barely proofread and filled with trite phrasing and typos, because when my emotions get the better of me, my MS symptoms flare up, which means my right hand has zero dexterity, it’s dumb as a fucking fist, and I hit the wrong keys.

“The Power of the Smaller Breast” was served up to me as new content today, but the piece was originally published in September 2024 and updated in February 2025. In addition to resurfacing it, The New York Times also reopened the comments, 100% knowing they could capitalize on renewed interest/reaction/sharing and the accompanying compulsion readers of all stripes would feel to add in their two cents. (Especially men. One of whom commented that if women didn’t like their large breasts they should “exercise more.”)

Here is my single cent; I don’t have the time for two plus I’m unemployed and being thrifty. My cent is not so much about the article itself, even though that’s what I wrote in my first sentence, but because of chasm between the “let’s consider this in a measured way” re: a woman’s right to choose breast reduction and the blistering hostility that gender affirming surgeries like top surgery are met with. Mutilation! Grooming! Whatever other dog whistle folks blow when they’re talking about trans people and their bodies!

Turns out, women are getting breast reductions at ever higher rates. Lisa Miller, the Times author, references stats from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons — surgeries are up 64 percent since 2019. This includes young women—girls—under the age of 19.

“The increase is reflected across all age groups, but especially among women under 30, who are enthusiastic consumers of plastic surgery in general, including face- and forehead lifts, procedures favored mostly by women their mothers’ age. Girls younger than 19 represent a small but fast-growing part of the market.”

The HRC tracks bans on gender affirming care, noting the scary rise in oppressive laws across the country but especially in Southern states like Texas, where I am from. These laws aren’t just aimed at trans youth—they target adults too:

[S]ome states, such as Oklahoma, Texas, and South Carolina, have considered banning care for transgender people up to 26 years of age. Additionally, several states prohibit public funds from being used to provide transgender health care for anyone, so adults are also unable to access critical health services if they receive their healthcare through Medicaid, if they work in the public sector, or are incarcerated.

Admission 1: I have a small chest. If I identified as female in any way I guess I would refer to them as breasts. Now, according to the NYT article, my chest is in fact perfect, totally the latest rage, 100% zeitgeist.

My mother and my sister were both fashion models (I KNOW, right?!) and when I was 15 or 16 my mom took me to a modeling agency to be assessed for the family legacy. This was just a hair before heroin chic took over fashion and so, as I walked the hallway away from and back toward the agency’s director, I noted how he turned to his assistant and ran his hands along his chest, miming the fondling of my own, shaking his head ‘yeah, no.’ Too small, he mouthed. Believe me I did internalize that for a long time.

Admission 2 (and this is the big one, especially considering my sister reads my Substack; I am now expecting a panicked phone call from my mother): I have wanted, forfuckingever, to be rid of my tiny chest. Even as I knew, through the buxom 1980s and briefly the 90s, that what I had wasn’t “enough.” Bigger is better! But I have desired since wee childhood to be able to wear a t-shirt with nothing underneath and not have people—especially men—gawk at the small swells and my nipples. I wanted my body to align with who I am.

This desire has become more urgent as I have gotten older and now, at 46, I am getting up the gumption to do something about it because (this is sad and fucked up) I can now also blame the rampant breast cancer in my family and claim that it’s also a precautionary surgery, not just gender affirming. Because I am afraid of judgement. Of being told that I’m throwing away my femininity (don’t want it! never claimed it!) and of being a target for even more transphobia and hate. 46, can you believe that? Decades to work up the courage to be me.

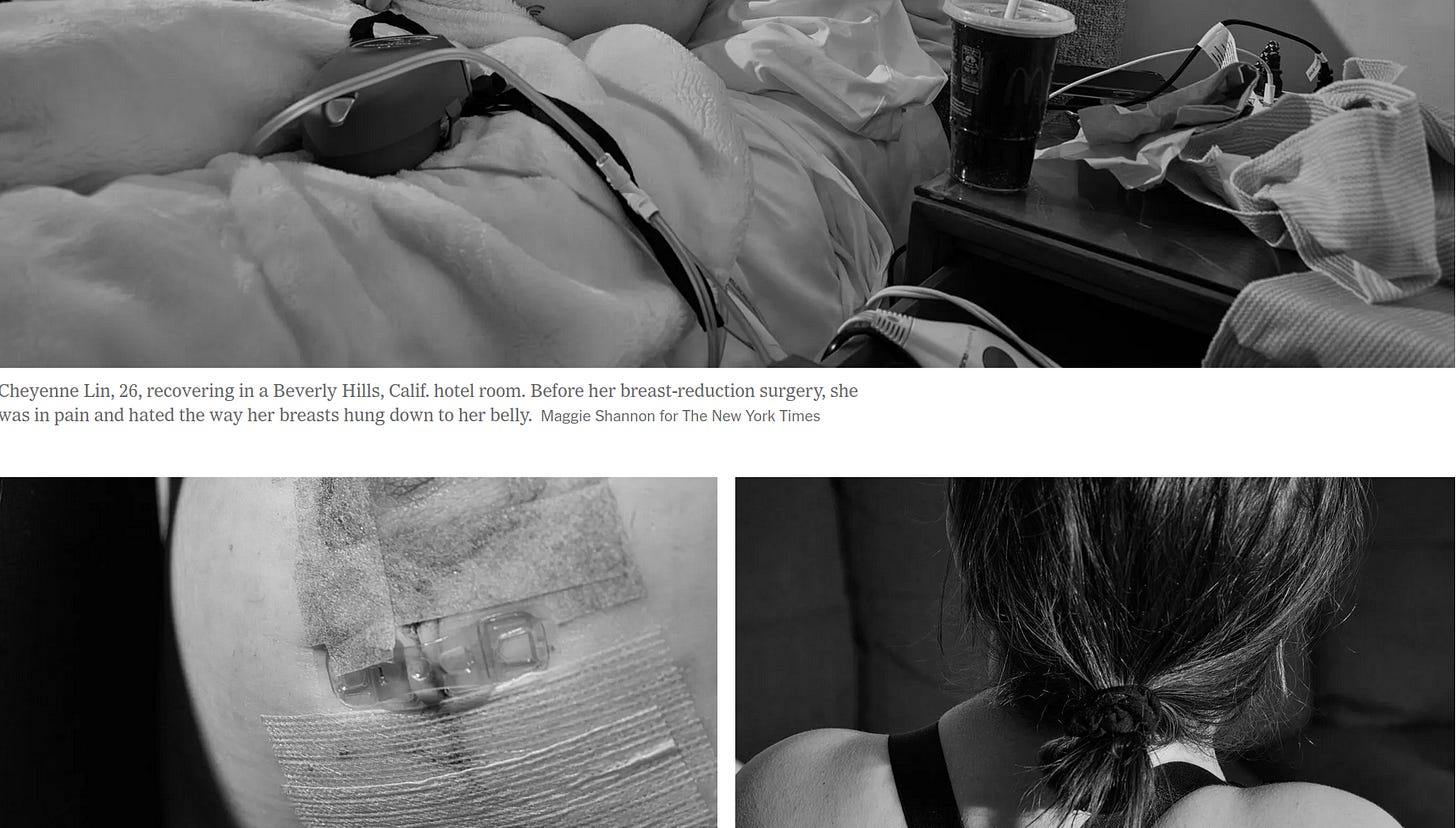

Meanwhile, Miller writes about a young woman whose in-laws footed the bill for breast reduction when the complexities of health insurance and access to a surgeon made finding good care impossible. I fully sympathize with this woman. She was in acute physical and psychological pain and made a choice that was right for her. Miller writes:

Starting around her sophomore year in college, she had constant searing pain between her shoulder blades. […] She couldn’t go hiking with her friends or snowboarding with Jaylen Lin, the exchange student who became her husband. Lin began to feel that she couldn’t participate in her own life; Jaylen even had to help her remove her clothes from the dryer. At 21, she said, “I felt like I was trapped in the body of someone in their 70s.” She was diagnosed with depression. [Emphasis mine]

After the surgery, Miller notes, “[She] considers the gift from her in-laws life changing. Her back pain is gone. She hasn’t taken antidepressants since her surgery.”

Meanwhile, so many trans people—youths and adults—struggle as I do with the shame of desperately wanting to change our bodies to not feel trapped, to be able to participate in our own lives, and to lift ourselves out of depression and dysphoria. Lawmakers want to stop us from doing that.

The societal cognitive dissonance is astounding and earsplitting. It rings out in every new legislative session where trans bodies and trans people are dehumanized, made objects, made to fear for access to health care and, with few exceptions, definitely not able to count on the sympathies of others to save us.

Every morning when I get dressed, I do layering math: are two t-shirts enough to hide my chest? Do I need a tank top too? What about some K-tape? I stopped wearing sports bras years ago because the compression made it hard to breathe and caused excruciating back pain. It also never felt right: even a sports bra was a bra, and I didn’t want to have to wear a bra. I just wanted to live in a body that felt like my body.

So it is with deep sadness and longing that I read a paragraph in the New York Times like

Or the choice to undergo breast reduction can be, in some paradoxical way, pragmatic. Perceiving, rightly, that she can’t change the culture she lives in, a woman might find that the easier path to loving her body is to alter herself. [emphasis mine]

and consider how when written in one context, the argument is that society forces some women to choose to breast reduction in order to love their body, while trans people who want to love their body because it is the body they deserve, that fits them the best, who want to use surgery or other means to love their body, are trapped by an argument we never started.